Anya Sinclair

The Tragedy of the Commons

5-24 July 2019

Anya Sinclair

The Tragedy of the Commons

5-24 July 2019

Anya Sinclair’s softly brushed images of wooded landscapes are drawn from the imaginary

of the internet. Some she has re-worked many times, changing scale and emotion. Most

have the watery indistinctness of Edwardian impressionist views of the bosky wildernesses

planted by Victorian gardeners to modulate their well-organised designs.

of the internet. Some she has re-worked many times, changing scale and emotion. Most

have the watery indistinctness of Edwardian impressionist views of the bosky wildernesses

planted by Victorian gardeners to modulate their well-organised designs.

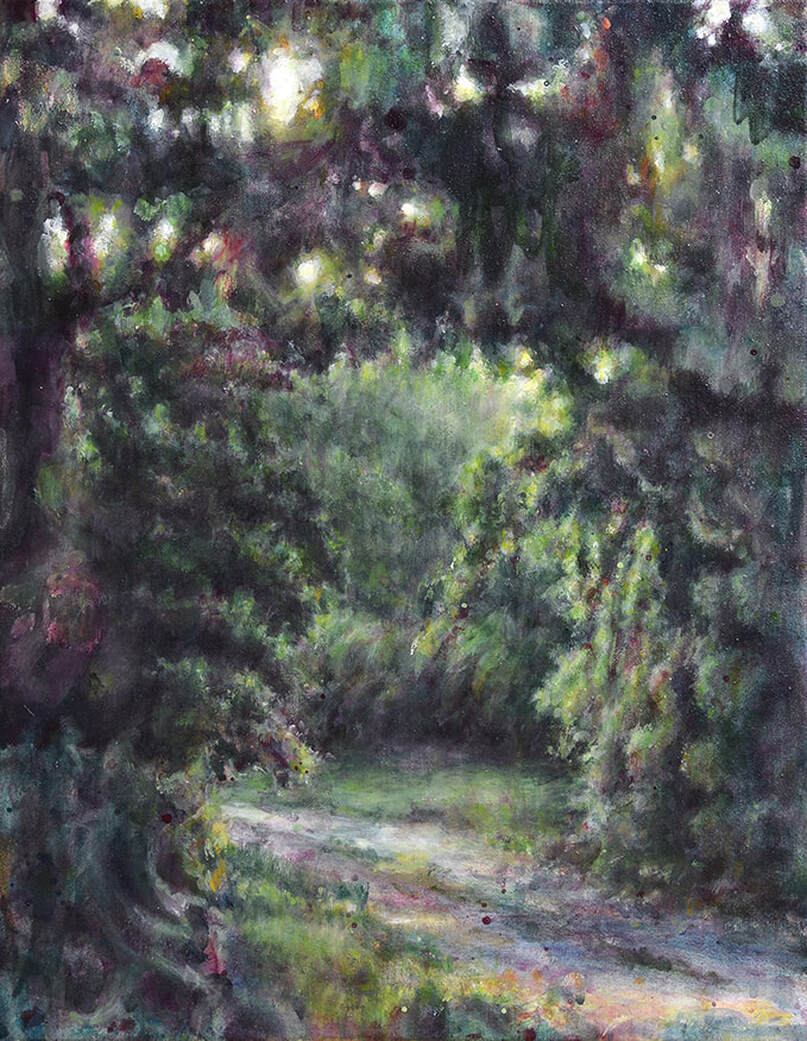

The Gloaming, 1300 x 1750mm. acrylic on canvas, 2019

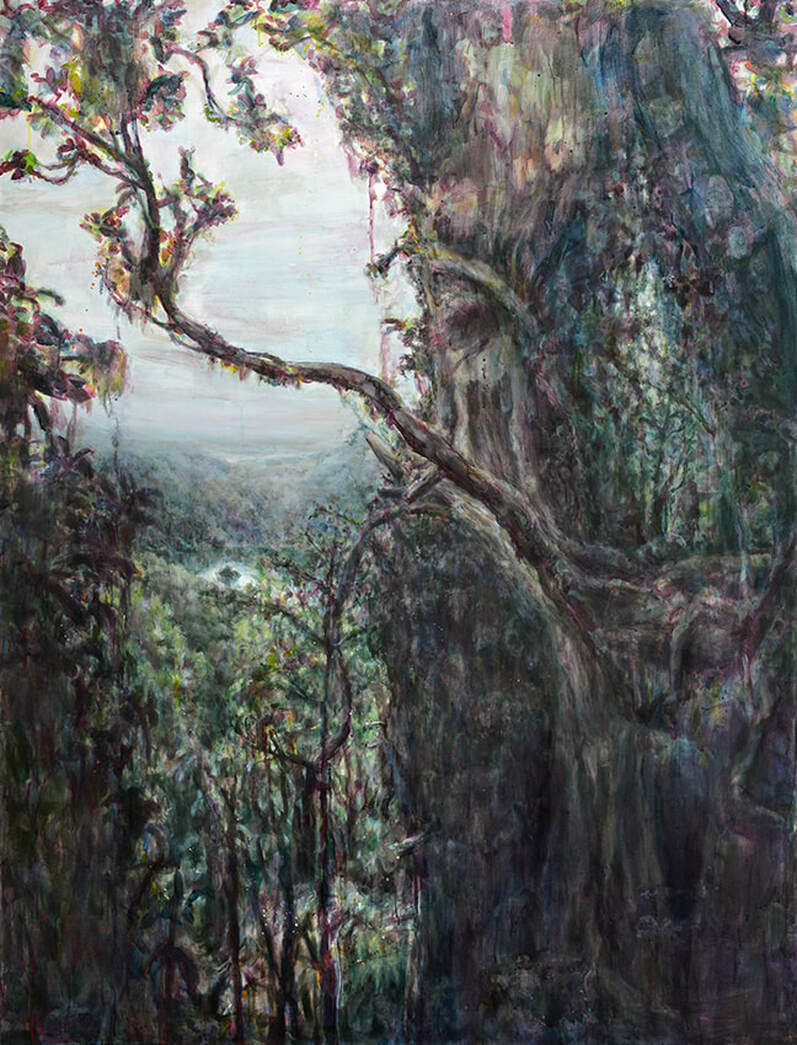

The Tree of Life, 1600 x 2100mm, acrylic on canvas 2019

Mirror Mirror, acrylic on canvas, 2019

The Tragedy of the Commons

Through her title, “The Tragedy of the Commons”, Anya Sinclair juxtaposes landscapes drawn from the imaginary of the internet, with Garrett Hardin’s critique of the very possibility of the collective conservation of resources.1 Woodlands frequently stand in for the idea of the commons in its initial, European legal sense as resources available to all, held in common. They harbour animals and provide the fallen wood that was once understood as being free to any gatherer. The provision of food for unpaid or barely paid labourers was left to the resources of the commons. When they were enclosed, or privatized, as in Britain during the late 18th century, those who had previously lived on their less valued elements – rabbits rather than deer, fallen wood rather than harvested trees – starved, or were forced to emigrate. The politics of the commons

1. Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons”, Science, New Series, Vol. 162, No. 3859 (Dec. 13, 1968), pp. 1243-1248.

apply here in Te Wai Pounamu. Many of those emigrants came here, where they did unto others what had been practiced on them, creating a servant class by restricting Maori ownership of land to unviable holdings.2

Garrett Hardin published “The Tragedy of the Commons” in 1968 as a plea for a limit to the population growth, which he called “breeding” that was depleting the planet’s resources. Fifty years on the extinctions, the pollution and the proliferation of waste he cited are understood as characteristics of the Anthropocene. Hardin believed that the conservation of the planet’s resources held in common was impossible because those who use such resources will consistently place their own interest before that of others. The farmer will graze a third cow, the fishermen will fill their nets, the person upstream will divert as much water as they choose, to the detriment of the pasture below. Similarly, people will produce more people. Self- interest will trump the possibility of an equal distribution of resources. Only mutually agreed coercions such as legislation and privatization will solve the problem.

2. Harry Evison, Te Wai Pounamu = The Greenstone Island : a history of the Southern Maori during the European colonization of New Zealand (Christchurch: Ngai Tahu Maori Trust Board, Te Runanganui o Tahu, 1993).

While Hardin’s primary concern was with population growth, the term is now more often applied to the abuse of resources he saw as its effect. However, when the Nobel-prizewinning economist Elinor Ostrom and her colleagues studied the management of fishing and water use in localized and indigenous collectives, they found that group thinking prevailed over individual greed in an overlapping network of reciprocity and care. 3 Hardin’s solutions were worse than useless: they exacerbated the problem.

The term is now as often applied to the digitised resources and systems of the internet Sinclair mines

3. Elinor Ostram, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015)

the digital commons for the generic landscapes apparently free to users, who may google “woodlands” and get a screen filled with images of trees, streams, pathways, and the occasional residential unit. The dig- ital algorithms appear to have an Edwardian sensibil- ity. Woodlands are usually framed according to the classical landscape photographic tropes of the sudden, stage-curtain-like transition from proximity to depth, or the occluded view, the pathway that turns, cutting the sense of the way out. The picturesque is alive in the digital commons, though it also may suddenly reveal itself as the property of Facebook or Getty Images.

Yet even apparently generic images can star- tle by their specificity. I know one of Sinclair’s views well, though she has never seen it. Taken on the way to Milford Sound, the image’s massive tree frames a sudden descent through forest to distant lake and misty skies before the road turns to the granite ridges of the Gertrude Saddle.

For a century, such views were emblematic of an idyllic, unchanging nature, a nature that at the same time provided all the resources humans might need. Yet a blood-like hue pulses though the greens of Sinclair’s landscapes. There is no going back to the delicate cli- matic balance and critical biomass such woodlands need. Last time I stayed on the Milford Road there was a sudden snowfall. The road was closed; trees fell for three days. The locals said this happens all the time, but I felt that these heaps of wet, red, freshly splintered wood indicated growth fostered by a warmer temperature, too weak to hold the snow’s weight.

Sinclair blots these splintering and disappearing landscapes with bloodstains and dried tears. Yet they also whisk us back to the world of the early twentieth century, with its desire to believe in fairies, to wrap some kind of tenderness around an already disappearing world.

Bridie Lonie, 2019.

Published on the occasion of the exhibition The Tragedy of the Commons: Paintings by Anya Sinclair held at olga gallery, 32 Moray Place, Dunedin from July 5th - 24th, 2019.

The illustrated publication was designed and printed by Point Design using a Risograph MZ770A and a RISO Comcolor 7050.

Through her title, “The Tragedy of the Commons”, Anya Sinclair juxtaposes landscapes drawn from the imaginary of the internet, with Garrett Hardin’s critique of the very possibility of the collective conservation of resources.1 Woodlands frequently stand in for the idea of the commons in its initial, European legal sense as resources available to all, held in common. They harbour animals and provide the fallen wood that was once understood as being free to any gatherer. The provision of food for unpaid or barely paid labourers was left to the resources of the commons. When they were enclosed, or privatized, as in Britain during the late 18th century, those who had previously lived on their less valued elements – rabbits rather than deer, fallen wood rather than harvested trees – starved, or were forced to emigrate. The politics of the commons

1. Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons”, Science, New Series, Vol. 162, No. 3859 (Dec. 13, 1968), pp. 1243-1248.

apply here in Te Wai Pounamu. Many of those emigrants came here, where they did unto others what had been practiced on them, creating a servant class by restricting Maori ownership of land to unviable holdings.2

Garrett Hardin published “The Tragedy of the Commons” in 1968 as a plea for a limit to the population growth, which he called “breeding” that was depleting the planet’s resources. Fifty years on the extinctions, the pollution and the proliferation of waste he cited are understood as characteristics of the Anthropocene. Hardin believed that the conservation of the planet’s resources held in common was impossible because those who use such resources will consistently place their own interest before that of others. The farmer will graze a third cow, the fishermen will fill their nets, the person upstream will divert as much water as they choose, to the detriment of the pasture below. Similarly, people will produce more people. Self- interest will trump the possibility of an equal distribution of resources. Only mutually agreed coercions such as legislation and privatization will solve the problem.

2. Harry Evison, Te Wai Pounamu = The Greenstone Island : a history of the Southern Maori during the European colonization of New Zealand (Christchurch: Ngai Tahu Maori Trust Board, Te Runanganui o Tahu, 1993).

While Hardin’s primary concern was with population growth, the term is now more often applied to the abuse of resources he saw as its effect. However, when the Nobel-prizewinning economist Elinor Ostrom and her colleagues studied the management of fishing and water use in localized and indigenous collectives, they found that group thinking prevailed over individual greed in an overlapping network of reciprocity and care. 3 Hardin’s solutions were worse than useless: they exacerbated the problem.

The term is now as often applied to the digitised resources and systems of the internet Sinclair mines

3. Elinor Ostram, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015)

the digital commons for the generic landscapes apparently free to users, who may google “woodlands” and get a screen filled with images of trees, streams, pathways, and the occasional residential unit. The dig- ital algorithms appear to have an Edwardian sensibil- ity. Woodlands are usually framed according to the classical landscape photographic tropes of the sudden, stage-curtain-like transition from proximity to depth, or the occluded view, the pathway that turns, cutting the sense of the way out. The picturesque is alive in the digital commons, though it also may suddenly reveal itself as the property of Facebook or Getty Images.

Yet even apparently generic images can star- tle by their specificity. I know one of Sinclair’s views well, though she has never seen it. Taken on the way to Milford Sound, the image’s massive tree frames a sudden descent through forest to distant lake and misty skies before the road turns to the granite ridges of the Gertrude Saddle.

For a century, such views were emblematic of an idyllic, unchanging nature, a nature that at the same time provided all the resources humans might need. Yet a blood-like hue pulses though the greens of Sinclair’s landscapes. There is no going back to the delicate cli- matic balance and critical biomass such woodlands need. Last time I stayed on the Milford Road there was a sudden snowfall. The road was closed; trees fell for three days. The locals said this happens all the time, but I felt that these heaps of wet, red, freshly splintered wood indicated growth fostered by a warmer temperature, too weak to hold the snow’s weight.

Sinclair blots these splintering and disappearing landscapes with bloodstains and dried tears. Yet they also whisk us back to the world of the early twentieth century, with its desire to believe in fairies, to wrap some kind of tenderness around an already disappearing world.

Bridie Lonie, 2019.

Published on the occasion of the exhibition The Tragedy of the Commons: Paintings by Anya Sinclair held at olga gallery, 32 Moray Place, Dunedin from July 5th - 24th, 2019.

The illustrated publication was designed and printed by Point Design using a Risograph MZ770A and a RISO Comcolor 7050.

''The Tragedy of the Commons'', Anya Sinclair (Olga Gallery)

It's been a while since we've had the pleasure of seeing an Anya Sinclair exhibition. She has returned with a fine display at Olga, which has much of the feel of her former work, but with an intriguing twist.

Sinclair's images still focus on the forested wilderness, rivulets of blue-green paint emphasising the humidity of the bush. Hints of rusted, sanguine red also permeate her scenes, suggesting simultaneously decay and life, and indicative of the delicate ecological balance of the world's lungs.

Against this living, sombre palette, the artist sets her theme, that of the tragedy of the commons - the idea that when faced with the choice between the good of all, or a larger personal gain to the detriment of the community, far too many people will pick the latter.

The slow deterioration of the environment is just such a situation. Sinclair combines these thoughts with the use of the commons in the more modern sense of the easy online accessibility of images, whether they be copyrighted or not.

Sinclair's images in the current exhibition feature subtle variations on a handful of such internet-accessed landscapes, allowing us the ability to compare the subtle differences between the images as we contemplate the fate of our current concepts of ownership and environment.

James Dignan, Otago Daily Times, July 18 2019