Philip Madill

The Informer

September 7 - October 1

Opening Friday 6 September

5pm

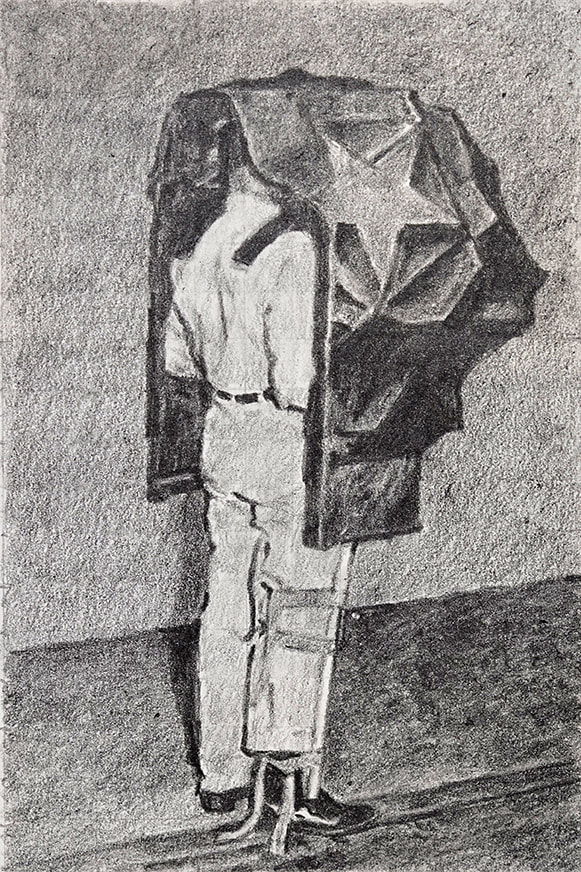

Philip Madill, Star Spangled Emperor, graphite on paper, 2019

Philip Madill’s The Informer

Philip Madill’s non-axiomatic compositional structures involve humans and objects in

relationships where meaning is partially buried. This response is an excavation of

sorts, without master narratives or tidy conclusions: partly because this seems like an

apt response, and partly because Madill’s work breathes in the interstices of meaning

and non-meaning. Madill’s work is displaced one remove from Luc Tuyman’s

“authentic forgery of reality.” 1 Madill’s drawings are rather, authentic seeming

forgeries of reality. The human subjects, and the objects with which they engage,

press the viewer to skein together a moment, an event, an interaction, but despite

Madill’s wilful urging, no such moment exists, or more accurately existed. Madill’s

graphite drawings elicit, or even more firmly, incite a sense of nostalgia without

clearly delineating where or what such fondness (or terror) for things past might

actually lie. In which era then might Madill’s humans and objects be located? The

thick, black-framed glasses, patent leather shoes, and space race-oriented apparatus

suggest the 1950s. The title of this exhibition, The Informer, points towards

McCarthy’s 1950s era of old fashioned surveillance, suspicion, and state informants.

Most drawings consist of a single human engaged in constrained or thwarted

relationships with a single object. The object incarcerates, camouflages, augments,

protects, seduces its human. It is also obdurate and absurd. The human appears to

have a fetishistic relationship with its object. Most objects assist the human in their

apparent desire to withdraw from the world, such as the man shrouded in a crinkly

cape (Star Spangled Emperor). The object appears to collude with its human to

exacerbate the production of a profound sense of isolation.

Despite the approximated historical markers, Madill’s non-axiomatic compositional

structures invite the viewer to enter “the space of what could be called its negative

condition – a kind of sitelessness, or homelessness, an absolute loss of place.” 2

Krauss was writing in the context of modernism, but arguably this negative condition

continues through postmodernism and onwards to post-postmodernism or wherever

we are now that the Artic and Amazon are on fire (and other inflammable realities

and hyperrealities). What might siteless or homeless subjects do? They might, as the

exhibition title suggests, secure their own safety by reporting the secrets of others.

Or, perversely, they might inform on themselves, whether in an attempt to escape or

deepen their isolation (it would depend on the distributed punishment). The latter fits

Foucault’s discussion of confession as a discourse ritual that takes place within

power relationships. 3 Do subjects excavate themselves beforehand, or does the

relinquishment of information take place in the interview between interlocutor and

extractor? Perhaps both? In The Interview, the hands of the subject reach into a

machine encasing the subject’s doppelgänger, or inner self. The self appears to be

reaching or searching for the self. The self squared.

Although Madill will have sourced some of the images for this body of work from the

Internet, and despite the inevitable digital transformation and dissemination of these

works, there is an obscurantist edge to Madill’s work. Executed in lead wrapped in

tree, Madill’s drawings seem immune to algorithms and big data. These ludic works

forged by mutations of the deep sovereign subject are algorithmically inaccessible.

This is a rupture.

Robyn Maree Pickens

1 Cristina Ruiz, “Luc Tuymans: ‘People are becoming more and more stupid, insanely

stupid’,” The Art Newspaper, 27 th March 2019.

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/interview/luc-tuymans

2 Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” October 8, 1979, 34.

3 Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. Translated by

Robert Hurley. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978, 58-62.

All works are framed with reflection control glass on hessian board.

''The Informer'', Philip Madill (Olga)

A first glance at Philip Madill's meticulously worked drawings might suggest that the artist has moved into new, happier territory in his latest series of works. Unlike his previous exhibitions, which have displayed dystopian images of a kafkaesque machine-controlled state, these works appear more open, more human-driven, and less submerged within the surveillance or control of technology.

A closer inspection, however, reveals that these are still people in some alternative-reality dystopia. We see an unnerving symbiosis or connection with machinery in drawings such as The interview. In other works - most clearly in Non-returned - we see images which would not be out of place in 1950s espionage films, or potentially in real-life espionage of the era.

Depictions such as the exhibition's titular work have a studied and claustrophobic air of repressed danger. Even the most emotion-laden and least machine-dominated of the works, the effective, audaciously composed The Self-confessed, has the same eerie air of paranoia found in the work of artists like George Tooker.

It is not just the disturbed atmosphere of these works which is worth noting. The skill of the artist and his ability to pick out fine detail impressively are shown to great effect in details such as the textured skin and reflective metals of Personal HAL.

James Dignan, Otago Daily Times, 26 09 19