Madeleine Child

Miranda Parkes

the new nice

5-23 October2019

Opening Friday 4 October

5pm

Madeleine Child

Miranda Parkes

the new nice

5-23 October2019

Opening Friday 4 October

5pm

this will be fecund...

Miranda Parkes "faith muscles" (acrylic, gold and silver foil, varnish on book page, 230 x 247mm) 2019

Miranda Parkes "flash in the pan vs Viva" (acrylic, gold and silver foil, varnish, nail polish, pVC tape, glitter tape on book page, 230 x 247mm) 2019.

Madeleine Child, Abstract lX, 2019

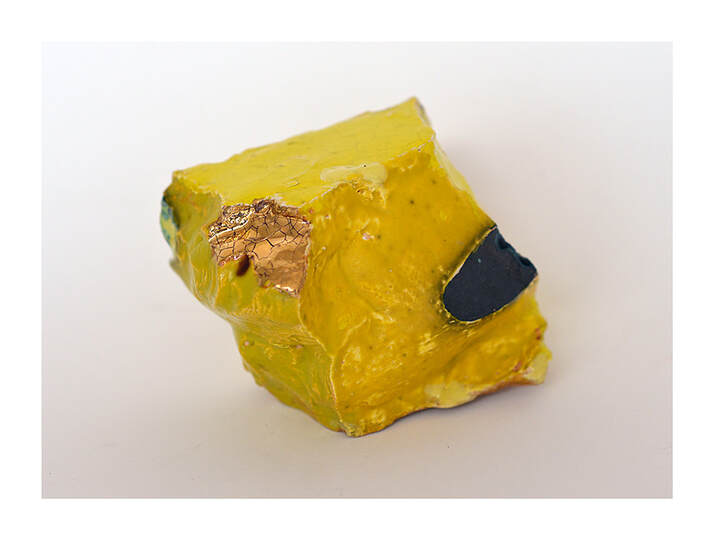

Madeleine Child, Abstract lV, glazed earthenware, 2019

“The new nice: détournement and recuperation”

The new nice takes yellow molten sheets of lava and forms architectural clods with

fine cracks showing beneath their glabrous skin. Each clod appears at once freshly

issued from volcanic flow and worked on in the ceramic artist’s equivalent of a forge.

Planar surfaces meet along soldered lines for functional joining or excessive

jouissance. A chip or area of rupture in the plane becomes a small slake of basalt, or

a gold-chipped, porcelain riverbed.

The new nice takes flat bookish surfaces and builds entirely new environments of

raised inflections formed through the relational encounters of paint, gold and silver

foil, varnish, nail polish, PVC tape, glitter tape, and collage. Through differing

degrees of density and viscosity these elements perform encounters of overlay and

overlap that play at concealment and revelation. The diverse fecundity of these

interactions as washes, serpentine lines, heavy stripes, and amoeboid splotches

sublimate, in most cases, the original image.

Madeleine Child’s ceramics and Miranda Parkes’ expanded painting practice are

brought together in this potential space of creative relationality. Their works are not

only relational qua each artist’s pre-existing body of work, but to the work made for

this exhibition by the other, and to the histories of art making. It is readily apparent

that both artists make work in relational response to the broad category of painterly

mark making collected under the wide umbrella of abstract art. Child’s ceramics take

in colour fields and line, edge, zip, and target, while Parkes engages with the

complete repertoire of abstract tools and techniques, from colour washes and blocks

to stripes, dots, and splotches. If Kenneth Noland is Child’s lodestar, then Robert

Motherwell is Parkes’. Child’s engagement with Noland is evident in her use of the

target as a means for colour experimentation, while Parkes’ collage paintings work

directly with all the plates from a book on Motherwell. If constancy is the main

attribute of a lodestar this does not preclude intentional deviation, and both artists

actively move away from their chosen source.

To a certain extent Child and Parkes present a détournement of Noland and

Motherwell respectively, but this détournement needs to be framed in the context of

the exhibition title, the new nice. As the title suggests, the artist’s “re-routing” of

Noland and Motherwell’s work is nuanced rather than violent. This is not a pitched

battle. Both Child and Parkes purposively take their respective lodestars out of the

rarefied arena of formalist abstraction and into everyday lived experience. They do so

with scale (most works are small in scale by the standards of canonical abstraction),

which in turn engenders greater approachability. Child and Parkes’ works welcome

the approach of the other. Their works exude warmth and encourage close

engagement with their materiality. Both artists deploy humour to welcome the viewer:

humour that is inextricable from the work’s genesis. It is present in the use of vivid

colour, and the embrace of the unintended or the accidental. These affective states

become part of the work itself, embedded in clay at the molecular level, infused in

paint before it dries. Child and Parkes move towards Noland and Motherwell even as

they move beyond the limitations of work produced in accordance with the strictures

of that era.

So if there is a generous and nuanced détournement at play in these two artist’s

response to their respective lodestars, Child and Parkes’ work also seemingly

engages with détournement’s opposite: “recuperation.” Or rather, the appearance of

the word “recuperation” in this dyadic relationship triggers instead the original

meaning of recuperation: “convalescence” or “healing” over its politically orientated

definition, which returns the object or act to the bind of capitalism. Rather than the

violence of “re-routing” and “hi-jacking” (détournement’s primary characterisation), I

am suggesting that the generosity bound up in Child and Parkes’ gentler

détournement simultaneously pulls towards, and invites a re-situated recuperation

that is directed towards healing over capitalist capitulation. To be sure, these works

are for sale (!) but this does not necessarily detract from the impulse on the part of

Child and Parkes to return to Noland, Motherwell, and canonical abstraction, the

qualities of warmth, everyday lived experience, and an open welcome to the

approach of the other, the viewer.

Child’s ceramic clods could rest comfortably in a large cupped palm. As objects of

alert matter they possess undeniable talismanic properties. In addition to the clods,

Child has produced a series of ceramic saucepan-like objects that approach the

functional in form, but in the same breath veer firmly towards art object. In our

correspondence, the name Child gave these works was “Kenneth Goes Domestic.”

The “Kenneth” is of course the aforementioned post-painterly abstract artist Kenneth

Noland, whose work Child has playfully détourned from high abstract formalism to

intimate art object. Child uses Noland’s target composition to superb effect, revealing

yet again her supreme skill as a colourist who uses colour to evoke spatial

movement, and relational invitation. Alongside her consummate skill as a colourist,

and her deployment of absurdist humour to destabilise hierarchy, Child’s saucepan

works are also reminiscent of adorned funerary goods buried with their owners to

accompany them into the next world.

Parkes’ collage paintings similarly transact between historical and contemporary

abstraction, and specifically with her “exploded book: Motherwell” works, she is

especially concerned with the intersection of the languages of abstraction and other

languages, even of language itself. This is evident in the titles of these works, some

of which borrow or incorporate Motherwell’s titles, and in the presence of words and

short phrases as both a physical and semantic layer in the collages. In some

instances the interplay of words, abstract languages or techniques, and Parkes’

relationship with Motherwell’s works take place over several “pages.” In the work

“cunt” (2019) for example, the titular word is collaged vertically and simultaneously

highlighted and overlaid by gold acrylic and foil. One work “cunt” is in particular

relation to is “dummy spitter” (2019), which features a large silver and gold O form

encircling one of Motherwell’s black circles from his Elegy to the Spanish Republic

series (1948-1991). These black circles represent either (or simultaneously) a bull’s

testicles or life and death. In “dummy spitter” a female form encircles a male, and

there is more than a hint of a feminist response to the male abstract artist still

typically reified in and as the canon.

In addition to the détournement and recuperation evident in Child and Parkes’

individual works in this exhibition, the two artists collaborated on a specific

assemblage. Titled “plinth (love is an open door) (2019), ” this work, which comprises

a readymade found and painted by Parkes, and clod sculptures by Child, provides a

clear instantiation of relational openness between the two artists. Open in gesture

and open in form the plinth assemblage offers perhaps the highest relational and

recuperative state: L O V E.

Robyn Maree Pickens

The New Nice. Madeleine Child & Miranda Parkes

Madeleine Child and Miranda Parkes combine in an enigmatic exhibition at Olga. Child's ceramics sit directly opposite Parkes' paintings, the two meeting tangentially in one collaborative item, Plinth.

Plinth sums up much of the exhibition: a single ceramic abstract, in the form of a highly glazed earthenware ''rock'', sits atop an elegant but tiny pedestal. We seem to be being told that a seemingly humble abstract is being raised on high as an edifice, but not so high as to be out of reach. We see low art, high art, and the shifting distance between them.

More of Child's rock-like abstracts adorn a wall of the gallery, seemingly placed at random. The effect reinforces the pieces' seemingly natural element, their artful artlessness. Child's work also includes a series of ceramic abstracts which can simultaneously be viewed as an ironic homage to the frying pan and as a more sincere nod to the target artworks of Jasper Johns.

Parkes' iconoclastic work is displayed on the opposing wall. The artist has taken pages from a book on abstract expressionist Robert Motherwell and used them as the canvas for her own abstract expressionist work. The bright, dynamic images occasionally reference Motherwell's images, and the effect is of a long letter, simultaneously honouring, defacing and ''improving'' the work of the 20th-century master.

James Dignan, Otago Daily Times, October 10 2019